Corruption Matters - December 2015 | Issue 46

Where is the sticky information in your organisation?

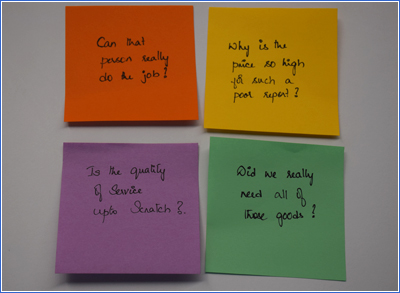

The integrity and effectiveness of government depends heavily on the diligence of well informed decision-makers. They should be able to answer certain questions, such as... Why is the price so high for such a poor report? Did we really need all of those goods? Is the quality of service up to scratch? Can that person really do the job? The answers to each of these questions could have thwarted corrupt behaviour that ended in an ICAC public inquiry.

It sounds simple but in reality the movement of information through an organisation to an informed decision-maker is often easier said than done. In highly centralised and formalised bureaucracies, information can be difficult to transfer and the expertise needed to interpret the information can be expensive to build at the centre of an organisation. The result is that useful information can be stuck at the coalface.

Often informal observations are interpreted by those in a given context, using their experience or expertise. In many ICAC investigations, for example, there were those in the organisation who suspected there were problems all along – that a training organisation’s graduates did not have the right skills, that inspectors had an inappropriate relationship with contractors, and so on.

The judgments may be more complex. When the ICAC examined the funding of human services through non-governmental organisations (NGOs), it became clear that managers on the ground not only had complex understandings of the integrity and service provision of NGOs, but also the viability of alternate arrangements.

Such a complex understanding, embodied in the tacit knowledge of staff, does not travel well within a bureaucracy of written reports, data and evidence. It is not suitable material for a report, and can come across as unsubstantiated opinion. Even if reported, the recipient of the report may lack the expertise to make sense of it.

The effect in centralised bureaucracies can be to separate the decision-making from the information needed to make the decision. Those who know the issues do not make the decisions, and those who make the decisions do not know the issues.

Yet, effective control demands that decision-making and the necessary information be brought together. If the information is sticky and cannot be moved to the decision point, then the decision point must move to the information.

This is exactly what the NSW Department of Family and Community Services is doing to better manage the risks in NGO funding. NGO financial information, which can easily be moved through an organisation, is routed to expert central analysts. On the other hand, assessments about NGO service levels are made near the coalface and are quite sticky judgments made by local staff. In this case, those aspects of the decision-making that relate to service are increasingly shifted closer to the physical point of service delivery.

In a potentially elegant solution, the decision process is split according to the stickiness of the information. The final decision is most likely to be made at the district level, using local assessment of service delivery combined with financial information transferred from centrally-located analysts.